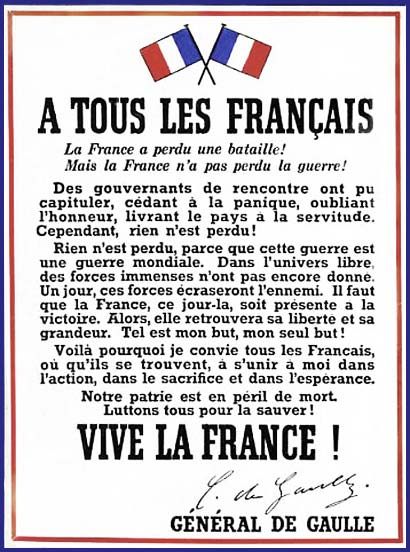

Affiche diffusée à Londres et en France en juillet 1940

© Mémorial Leclerc – Musée Jean Moulin

Of the Second World War and the role played by the French army during this tragic time, the French collectively only really remember the defeat of 1940.

We know that the French army suffered a spectacular defeat, thanks to the errors of its high command and a fearful government. The government had taken the imitative to declare war on Germany on 3 September 1939, but it hesitated to launch any serious offensive until 10 May 1940, the day the Germans invaded Belgium. French procrastination was swept aside by the Blitzkrieg (lightning war).

Policies

With an army that had been defeated in five weeks and the irresistible German advance, the supporters of the armistice overcame the few politicians who wished to continue fighting (such as Georges Mandel or Paul Reynaud, the president of the Council, who resigned on 16 June 1940 under pressure from those in favour of the armistice),

and also the only soldier who ardently wished to continue the war, General de Gaulle, who was very isolated in the days preceding the armistice. The convergence of his views with those of the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, led him to flee to London.

After the armistice of 22 June 1940, France was cut in two by a demarcation line. Its political and administrative institutions remained in place and occupied France was under the control of a government formed by Marshal Pétain in Vichy. Two thirds of the territory of metropolitan France were under German occupation.

With the Law of 10 July 1940, Parliament granted the widest powers to Marshal Pétain, thereby conferring legitimacy on the new regime based in Vichy. With this constitutional law, Parliament, which included members who had been elected in 1936 (in the election that brought the Popular Front to power and that made possible major social advances such as paid holiday and the 40 hour working week) brought an end to the III Republic, which had lasted for nearly 70 years. Power was handed to a man of 85.

The new regime included many politicians from previous governments (and therefore a large number of men from both left and right of the political spectrum), trade union leaders and young technocrats who achieved a certain kind of fame in the Vichy regime for the wrong reasons.

The french empire

It is important to remember that in 1940 France still had a very large colonial empire. Apart from Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, France was also present in Lebanon, Syria, Equatorial Africa and South East Asia.

Because of this, a large number of troops were still stationed in Africa. Some of these troops took part in the fighting in 1940 in France and Belgium. After the armistice the African Army was demobilised, but it constituted a large reservoir of men.

In theory, the African Army remained loyal to Vichy. It abided by the law, but thought of revenge, particularly under the influence of many officers who were to play – in varying degrees – a double game (particularly General Weygand, General Juin, General de Lattre de Tassigny and General Nogues).

On the other hand, the African Army remained particularly hostile to General de Gaulle, who was thought to be pro-British and manipulated by them. The destruction of the French fleet by the British at Mers-el-Kebir in July 1940 did not make his task any easier. A refugee in London, from where he launched his famous appeal of 18 June 1940, General de Gaulle had little, indeed no, legitimacy with the army. The Syrian campaign in 1941, in which the French managed to fight each other, with the African Army fighting against the British and the Free French, illustrated this very real civil war.

The entry into the war of the United States

Photographie extraite du film Pearl Harbor

© Touchstone Pictures et Jerry Bruckheimer, Inc.

After 18 months of occupation, the Second World War entered a new phase with the entry into the war of the United States after the attack on Pearl Harbor (7 December 1941).

The African Army was awaiting its moment. In 1942, the Americans made contact with the French officers who were present in the Maghreb, through their representative in Algeria, Robert Murphy. At the time the Americans had no faith in de Gaulle. The American president, Roosevelt, regarded him as a dictator in waiting and did not conceal his suspicions from Churchill. The Americans thought that General Giraud, who escaped from prison in Koenigstein in April 1942 and who seemed more manageable, was a better bet. Secret contacts were made by Eisenhower with Giraud in 1942, and then by General Mark W. Clark with General Mast in October 1942. It is important to understand that de Gaulle had strictly no influence on the events that were to take place in North Africa at the end of 1942.

The Americans landed in Algeria and Morocco on 8 November 1942, in an operation code-named Torch. Some French officers of the African Army, however, seeing this as an opportunity to make a “last stand” in an attempt to salvage their honour, attacked them. The period is problematic and the Allies’ subsequent victory over Germany was by no means certain at the time. After the war some maintained that the African Army really had fought for its own honour. However, nearly 2,000 French and American soldiers lost their lives and the ceasefire between the French and the Americans was only concluded after several days of fighting (particularly in Morocco), in the most total confusion. The sincerity of those who made this “last stand” must therefore be open to doubt.

Against all expectations, the ceasefire and the maintenance of French sovereignty in Algeria and Morocco were confirmed in agreements concluded by General Mark W. Clark and Admiral Darlan, who was in Algiers at the time visiting his sick son, Alain. Faced with the incomprehensible procrastination of General Giraud, Admiral Darlan, Minister of War and vice president of the Council, who had collaborated militarily with the Germans, sided with the Americans in November 1942.

Because of his obvious political sense, his undoubted diplomatic qualities and undisputed authority over the African Army, the Americans could not ignore him. Nearly two months after operation Torch, his assassination on 24 December 1942 by Fernand Bonnier de la Chapelle was certainly not the act of an isolated assassin, as some maintained. We now know that there was a royalist plot against him, that was sustained and financed by the Gaullists. If de Gaulle was not directly involved in the plot, it has been shown that Gaullists took part in the plot if they did not organise it.

Had Darlan lived, it is certain that things would have turned out very differently for General Giraud and General de Gaulle, whose political future would certainly have been compromised. This assassination, which was almost certainly political, thus had a major impact on the course of events at the end of 1942 leading up to the Casablanca conference in January 1943.

The presence of the Americans in North Africa was to open new possibilities for the African Army led by General Juin. From then on, he fought consistently for the French to take part in the war against the enemy that had become their common enemy.

The French army, which was very poorly equipped, then took part in the Tunisian campaign at the beginning of 1943, which was intended to liberate Tunisia and drive the Africa Korps out of Africa. This was achieved in May 1943 after several months of fighting (in which the 4th R.T.T. were involved). It was against this background that the Allies decided to launch their invasion of the Reich by landing in Sicily (operation Husky) in July 1943, and then in Italy (operation Avalanche) in September 1943. This was the beginning of the long Italian campaign of which the Battles of Monte Cassino and Belvedere formed part.