German 75 mm anti-tank gun knocked out, Cassino – D’Arcy Whiting- 1944 – Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Käwanatanga – Wellington Office – AAAC 898 NCWA W598

Hill 862 was the “cornerstone of the Belvedere”

(général Chambe – Le Bataillon du Belvédère).

It was cold and misty with an icy drizzle at dawn on 26 January.

2nd Lieutenant Bouakkaz said to Lieutenant Jordy “I’ll be the first to get up there” pointing to hill 862. Bouakkaz and Jordy identified hill 862 and its twin hill a little lower to the right which they called the “Peak with no Name” for reconnaissance purposes. Jordy’s men were tired and had already run out of water. They hadn’t eaten for thirty hours.

Lieutenant Jordy was aware that the Germans would organise a counter-attack, that he was at risk of being isolated and, above all, that they had almost run out of ammunition. His company was also the most exposed to the enemy positioned on Cifalco. Gandoet informed Jordy at dawn that he would make for hill 681 with the 10th Company (Louisot), the support company (Jean) and two companies borrowed from the 1st Battalion as a reinforcement for the 11th Company (including the 2nd Company (Billard)).

At the same time, French and American tanks were patrolling to retain control of the valley.

The 3rd R.T.A., which had arrived overnight, gradually took over from the 4th R.T.T. in the valley.

At 2.00 p.m., the men commanded by Gandoet contacted the lookouts of the 11th Company. They could partially resupply the 11th with ammunition but not with food. The 2nd support company (Aygadoux) arrived on hill 681 at 3.00 p.m.

Colonel Roux gave the order to attack hill 862 at 4.30 p.m.

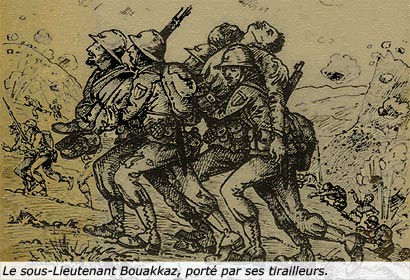

Jordy received the message at 4.35 and launched his men immediately. Sub-Lieutenant Bouakkaz marched at the head of his men as he had requested. He attempted a wide flanking movement to the right. The support company under Captain Jean covered Bouakkaz with mortar and heavy machine-gun fire.

Unfortunately for the French, the Germans behind the lines had anticipated the French attack and the 11th Company was met with an incessant hail of bullets, shells and mortars. The Peak with no Name was transformed into a huge and murderous firework display. The Germans fired from Cifalco and from hill 470 (which they had recovered from the French). The 11th Company suffered serious losses, but the French artillery covered Jordy’s men effectively. The shelling lasted for more than two hours.

The Huguenin section of the support company followed the 11th Company, along with the 10th Company (Louisot) and the 2nd Company (Billard).

The sections led by Bouakkaz and Nicolas advanced under German fire and managed to take first of all the Peak with no Name.

Dessin de Paul Devautour

Bouakkaz was killed by a bullet in the temple on the Peak with no Name. Sergeant Mohammed ben Abdelkader removed his body and, assisted by two other men, placed it sitting up on a gun which they carried, one by the butt and one by the barrel, up to the summit of hill 862. Bouakkaz had sworn that he would reach the summit of 862. Which he did, dead, carried by his men under German fire.

Excerpt from “Bataillon du Belvédère”:

Then, before laying it down on the land he had conquered, they stood up their officer’s body and held it an instant facing the enemy. Then they laid it down gently among the rocks, the face turned towards the German line.

At 7.00 p.m., hill 862 was taken by Jordy’s company. This confirmed the breaching of the Gustav Line by the Allied army, or to be precise, by the French army.

Fighting involving the 2nd battalion

The 2nd Battalion (Berne) crossed the Rio Secco – when the men were up to their waists in water – and then went up the slopes south of the Belvedere to the left. The 2nd Battalion’s objective was to take hill 382, then hills 700 and 771 and Casale Abate (hills 915 and 875).

The village of Cairo was taken by the American 34th Infantry Division supported by Sherman tanks and the artillery of the Bonjour group. 7th Company (Tixier) made rapid progress to reach its intermediary objective, hill 382, which was close to the winding road that linked the village of Cairo (90) to the village of Terelle (902).

7th Company (Tixier), 6th Company (Thouvenin) and 5th Company (Chatillon) rushed forward, followed by the support company (Isaac). 7th Company took hill 382 first of all.

2nd Battalion did not have a Gandoet Ravine to protect it. From hill 302 it had to advance without cover from the German artillery. 7th Company was to engage towards hill 700. Major Mengus’ 155 mm guns covered Captain Tixier’s advance.

Tixier’s Company took hill 700 at nightfall, and was then counter-attacked by the Germans. Tixier retook the hill 20 minutes later using bayonets. Tixier, like a great officer, went into battle at the head of his men. Counter-attacked a second time, hill 700 was evacuated by the French but was not retaken by the Germans. Tixier took several prisoners who belonged to the 131st Pomeranian Infantry Regiment, like those captured by the 11th Company.

6th Company (Thouvenin) meanwhile advanced along the southern slope of hill 721. Like Tixier, Thouvenin willingly went into battle at the head of his men to reassure and encourage them.

Excerpt from the “Bataillon du Belvédère”:

Major Berne later wrote of his officers and men:

Thouvenin took the base of hill 721 and managed to begin a flanking movement to the left, but with the close of day, was forced to suspend his advance.

Monsabert sent a battalion from the 7th R.T.A. to hill 700 as a reinforcement and a battalion from the 3rd R.T.A. above Olivella facing Belmonte.

Major Berne was wounded by a piece of shrapnel that fell near his lookout post. The body of his artillery cadet, Garner, was cut in two. Berne passed out but not before passing the command of the 2nd Battalion to Captain Léoni, who then made contact with Jordy and Thouvenin. The men still had nothing to eat or drink. It was 10.00 p.m.

The artillery fire resumed in the night. The riflemen were not able to assist the wounded as this time the German artillery did not let up.

Excerpt from “Bataillon du Belvédère”:

Now the Germans were no longer shooting to harass, they were shooting to halt the enemy advance with massive and uninterrupted shelling. Not a scrap of land was untouched by the impact of the huge shells. In the light of day the slopes would look like the moon. The men could only escape the destruction by hiding among the rocks in the shallowest depressions, praying for a little luck.

The wounded who were able to, dragged themselves to shelter as best they could, others lay where they had fallen. Throughout the night, in the rare moments of silence, their groans and pleas could be heard. Some of the men, no longer able to leave a dear comrade whose voice they recognised, threw themselves into the darkness, at their wit’s end, like mad men, to help the wounded. Many did not return from their heroic attempts.

Captain Léoni (who had replaced Major Berne) received the order from Colonel Roux to attack the summit of Casale Abate (hill 915) at 4.30 p.m. in the afternoon of the 26th.

Léoni mobilised his three companies: 6th Company (Thouvenin), the support company (Amiel), and 5th Company (Clément replacing Captain Chatillon, who was killed on the first day of fighting). Léoni was unable to call the officers together given the intensity of the shelling. They were obliged to meet 30 metres apart and to shout to make themselves heard.

The 2nd Battalion was to take peaks 718, 721 and 771 before tackling the ascension of Casale Abate. The advance was made under fire from Cifalco and Cairo. The losses were enormous.

Léoni asked permission from Colonel Roux to take a break given the men’s exhaustion. Around 9.00 p.m. Colonel Roux refused. The risk of a German counter-attack was too great and the men had to continue their advance in spite of their fatigue.

Léoni’s men therefore resumed the ascension of hill 915 surrounded by exploding mines and under a barrage of rockets from the nebelwerfer.

The losses were appalling. Captain Izaac, commanding the support company, was “blown to smithereens” by a mortar. 2nd Lieutenant Mohammed, section chief, was killed. The Cadet Carbonnel, also a section chief, was seriously wounded. Lieutenant Thouvenin was killed. Corporal Conrad and Sergeant Le Guen were killed. On the summit of Casale Abate there were around 150 survivors, with almost no ammunition. But at 2.30 in the morning on January 27th, Captain Léoni and 2nd Lieutenant Clément took the summit of Casale Abate, hill 915.

Sergeant Klausner sent up a flare: the objective had been reached.

The summit offered no cover: it was impossible for the men to dig trenches or raise walls. Casale Abbale consists of stone slabs, with very little soil. Sleep was almost impossible.

Fighting involving the 1st battalion

The 1st Battalion, which remained in reserve initially, received the order, at the end of the day on 25 January 1944, to cross the Rio Secco, defend the Olivella position, and then climb the Belvedere in order to reinforce the offensives led by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions.

The 1st Battalion was supported by a squadron of tank-destroyers from the 8th African Armored Regiment and a company of American tanks.

After crossing the Rio Secco, the 1st Company (Lartigau) and the 3rd Company (Carré) first cleaned up the Olivella sector at nightfall.

Major Bacqué then launched the 1st Company (Lartigau) up a mule track which led to hill 382 in order to support the 2nd Battalion. The men had to walk in single file in the darkness, holding on to the jacket of the man in front.

Meanwhile, Bacqué had lost contact with the 3rd Company. He then decided to set up his H.Q. in the valley in the houses at Olivella. This position would prove to be particularly exposed to the German artillery.

At the same time the company led by Carré was to follow in the steps of the 11th Company, except it had to do the climb guided by a compass and at night. The men crossed the Rio Secco in deep water. They were going to do this nocturnal climb soaked and frozen. The men could hardly see 2 metres.

Lieutenant Carré made notes in a notebook that he kept with him (night of 25 to 26 January):

At 11.10 p.m., the 3rd Company reached the summit (this seems to be hill 382).